An interview recorded by Gabriella Giannachi and Nick Kaye on 8 March 2006, edited by Nick Kaye

Mike Pearson: In the large-scale work of Brith Gof we eventually identified a real problem for the performers. As the scale of the work grew, so the performers simply became one element in the mix of the performance. And it’s a very difficult thing for the performers to accept that they are not the sole carriers of meaning in the work. For instance, in that large-scale work it may have been the soundtrack that was creating the emotional tenor in any one section. And those of us performing increasingly felt like ciphers - we were often so far from the audience that we couldn’t measure any response to what we were doing. We became rather lost in the mix. We did talk about that quite candidly, and that was one of the reasons why I then started to make small-scale, personal work - to try and understand what it was to work directly with an audience again, very intimately. In the work then that Pearson/Brookes has done, we’ve tried to find a place for the performers - albeit by asking them to deliver what they do for very short periods of time, or in unusual circumstances - but always to value that. And certainly the performers that we’ve worked with regularly have been willing to accept that. It is quite a thing to ask John [Rowley] from Forced Entertainment or Richard Harrington - who is a very well known TV actor - just to sit, to sit in a certain way. We have attempted to recover the performer, tried to find a way of assuring the performers that their work will be placed in some kind of an appropriate context. That was a real eye-opener for Ed Thomas’s five performers in Rain Dogs (2002), to work like that for the first time and then to see themselves placed appropriately.

Rain Dogs, 2002

Gabriella Giannachi: I am interested in the relationship between ‘presence’ and doing nothing - or that moment in which you draw attention to someone who is just about to do something - or is potentially going to act. What is it that draws you to these kinds of moments?

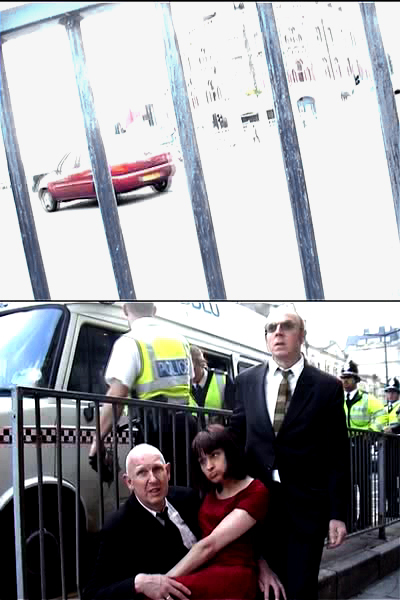

Mike Pearson: With this ‘doing nothing’ in the street - or sitting with the camera - we were interested to see what resources of the actor are brought into play. Of course, it is not simply standing and doing nothing as someone would who is not trained in particular ways. That’s one thing. But I am also very interested in that moment of – ‘Here we go’ as well - or ‘Here I go’ - that moment just prior to doing something. Maybe we actually tried to confound that, purposefully. For instance, in the footage of Rain Dogs - the CCTV footage from the street - the performers only knew within a certain envelope of time when the camera would come and look at them. And in that, that kind of emergent moment of ‘Do it now’ would be compromised. I was perhaps more aware of that ‘moment prior to doing something’ in the large scale Brith Gof work, where very often the performance was particularly arduous and I could see us all going ‘Oh no!’ and then - in the moment - really delivering it because there was no other option. Maybe that’s what we are always trying to bring about, those situations where there is no option - either you do this or you don’t do this - there’s no half-measures here. [TO MIKE BROOKES] Maybe you aren’t too worried about that?

Mike Brookes: It’s a different relationship for me. For me, when we started working together, it was simply that there were two of us in a room, attempting to evoke something that functioned. And the work that we were individually doing to sustain that happened to differ in nature.

The First Five Miles, 1998.

Gabriella Giannachi: How do these ideas relate to the site-related work of Pearson/Brookes that you first presented today, for example The First Five Miles (1998)?

The First Five Miles, 1998.

Mike Pearson: In one sense there was a question again about scale. So, The First Five Miles was at the largest scale I could imagine making work - operating in a fifty-mile radius. But, actually, it was only created in the detail - in my ability to deliver in this moment, when Mike said ‘Three, two, one, go!’ I don’t know whether that answers the question, but I am not sure I was even conscious, in The First Five Miles, of the particular story that animated me: I was interested in the parliamentary enclosures. But it was always questions about how do we make work in this context, rather than attempting, consciously, to break or depart from the architectonic model, which had been with Brith Gof from 1989 or 1988 through to the mid-90s. It was always a response to a question or to a problem. I like Mike [Brookes]’s model of there being a piece of work and audience and all we have to do is make a bridge between the two – or, you know, how do we make this available to those people?

Dead Men's Shoes, 1997

Mike Brookes: In my recollection of The First Five Miles it wasn’t that different from performing Dead Men’s Shoes (1997). I don’t remember having developed that on/off thing. I think we started and, maybe because you wore costume, or because we were walking, there was no chat between us, even in those moments when we weren’t being observed. It was a very focused thing.

Mike Pearson: That’s right.

Nick Kaye: We were both very struck by your proposal that ‘in the space between presence and absence lies the archaeological imagination’. What does it mean, as a performer, to think of the presence of the body archaeologically?

Carrying Lynn, 2001

Mike Pearson: One thing is the way in which one’s physical presence in performance is the result of a whole series of historical moments and processes that one has gone through - of training and so on. In 1980 I studied noh theatre in Japan and I really do feel that experience is embodied in how I am – in certain predilections or desires for stillness from time to time or in cutting the text from the action for instance, those kinds of things. That’s the first thing - there is a bodily archaeology in that sense. Whether one can escape from that is a whole other question - and whether you know you are trying to escape from some kind of disciplinary regimen that you’ve acquired. The second thing is body scars; I am fascinated by performance injuries and accidents. I have the feeling that when performers get together to talk about past experiences, they only talk about the bad times. Very, very rarely do they actually characterise their ‘presence’ when it was going well. They often talk about those moments when the thing fell to pieces, when somebody forgot to do something, when the set fell over: all of those times when they actually had to use their ability to assert their presence, or to prevent the thing from falling apart. So there’s a kind of hyper-awareness in this kind of situation. Some performers do think about other performances they’ve done as they are performing. I wonder what’s happening to performance artists who work in very long durational pieces, for instance. Where do they ‘go’ during those works? Are they always ‘present’ during that duration? Are they remembering similar experiences, different experiences, and so on that are enhancing this kind of moment? Then, I guess, you do archaeologically also in terms of assembling bits of this and that that are necessary in this moment. Maybe this comes from what we were talking about – from one of the themes today about fragmentation and assemblage. Actually asking: What fragments of what I do are necessary in this moment to bring about the effects that I want to bring about, if I am not working with character, motive or dramatic interpretation?

Nick Kaye: Do you think of presence as a technique?

Mike Pearson: I know Mike’s partner Jill Greenhalgh does. A lot of the work with our first year undergraduates is about presence. Much of Jill’s work is on obstructions - and is, basically, a kind of… ‘No, don’t do that,’ ‘No, don’t do that’ - until one is focused to a point where you think, now what am I doing? I am a little bit ambivalent about it, having worked with a number of people who I think are completely ‘absent’ in fairly serious ways - Peter Brotzmann, the German saxophonist, certainly in the first five years I worked with him - and yet who would always in the performance deliver the goods. There were two interesting things in working with him. One was that he had no notion of rehearsal. If he was doing it, he was doing it. And he would do it 100%. Now, whether it was instinct on his part by that time but – we have already talked a lot about that. There are certain genres, like noh theatre, where the particular ‘obstructions’ of the form lead to notions of presence as a kind of technique – well, not really as a technique. It’s probably one of the things that I do agree with Eugenio Barba on. I do think the creation of a particular kind of body for that art form - and it’s the only one that I know in any kind of detail - does lead to a heightened awareness of what you are doing because the rigour of making the body shape is enormously concentrating.

Gabriella Giannachi: I am interested in the relationship between this notion of obstruction and the document or documentation, as well. In your performances, many of the events are only available to the audience through real time recordings brought to the theatre, or video of past events. Is this linked to this notion of archaeology?

Mike Brookes: It’s a very simple point, but there is a very particular relationship to the CCTV footage in Rain Dogs, especially the city stuff. The material stops becoming a staged event and becomes something that actually happened in the city. People relate to that footage in a different way. We read it in a very different way, I think.

Mike Pearson: How do we live with the detritus of that event? Maybe that is purely archaeological in the sense of: How do I interpret it? How do I deal with it? It was very instructive in the few moments that I was able to talk to the police video operator of the CCTV about what he was looking for. As we were saying before, he is looking for that moment when something will transform into something else. Otherwise he is just a voyeur of past events. You are always looking at the potential for something - the potential for crime. One of the indices of that is a person doing nothing. So he really is constantly looking for people doing nothing - may be sitting in the street or standing in an inappropriate relationship to something else. That’s what he’s trying to identify.

Nick Kaye: One of the complexities in the work – linked to the archaeological - seems to be an exploration of the layers and dislocations in time and place that define a site - which means that the site can never be fully present. It seems to me that in these performances, in which you re-present in one place material developing in an earlier time or another space, that you take that notion of site on very directly. I wonder what this complexity of site might say about the performer?

Polis, 2001

Mike Pearson: There were a couple of things…The first is whether the presence of the performer serves to reveal an architecture – or a series of places – anew, and in a quite different way from the way we used to work [in Brith Gof]. I do remember certainly in works like Polis (2001) and I am sure in Carrying Lyn (2001) a lot of the response of the audience came from identifying places they knew, or else places just adjacent to places they knew but were unfamiliar with. These places were being revealed by the presence of the performers - by putting performers into a particular kind of context - and then you see that context. So constantly the response was, ‘Oh look, there they are in front of,’ ‘Oh look, now they’ve shifted, where’s that?’ ‘Where’s that?’ This presence is just revealing these places. One of the themes that we didn’t talk about a lot today is this notion of ‘archaeologies of the contemporary past’. What our performers do - sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly - and we have made a number of projects which are more directly pertinent to this - is that they point directly to detail within the fabric of sites. Pointing, for instance, to their multi-temporality or the mark-making of others who have gone before in those places… So, many of the texts for Rain Dogs - which we wrote after seeing these performers in these places - were very much about that – about trying to think about the multi-temporality of places, as I said, and actually pointing out the places where bodies have worn into the city - the bodies of others - but in this landscape that we live within. I remember some of the texts from Rain Dogs: in one I became very interested in the fact that our city [Cardiff, Wales] is very shallow. It’s a fairly new city and almost all of the southern docks area is built on ships’ ballast. So it’s got no real depth - you have an exotic geology that is just under the surface. I’m also interested in the former usage of places - and how you can do that very lightly without necessarily having to re-enact anything. Ten or fifteen years ago we would have been working out how to refer to these places in some form of substantial way.

Polis, 2001

Mike Brookes: The other side of that, in terms of my preoccupations, is how you tap into, and place those events [so they can be encountered by an audience]. How you construct that quality and that depth of material - which is inevitably what I am trying to do by mixing those fragments and moving the material around [for an audience] - to evoke that sense of a place, where a particular sort of meeting or a particular sort of revelation can happen for those of us that are there at the time. On the understanding that that construct will only exists for the duration of that mix…

Nick Kaye: So a transcription of one place into another place?

Mike Pearson: No. I think the creation of a new place by tapping into those things.

Gabriella Giannachi: I’m interested in what this process might mean for the interplay between mediation and presence?

Polis, 2001

Mike Brookes: When I think back to Polis, there were a lot of things that were not present within the room; but we were trying to draw things from the city in a much larger sense. We were trying to give that sense [of the city] a presence in a tangible way, by revealing moments of its reality. In staging a work like Polis it was as much about joining that studio space with the city as it was about marking its distinction from it.

Mike Pearson: In the mix or the ambience of the whole thing, none of the elements go unregarded. As Mike said, finally working out where he might put different orders of sound in the room, for instance. I think we are trying to create an experience very directly for an audience, but this mediated material doesn’t demand that you make a direct response to ‘’this’’ video image, because it is already located in relation to three others, and to the sound envelope in the room, and so on. So whilst it’s very clear that actors are doing very serious things, one’s response might be shaped by this combination of things that is going on in the room.

Polis, 2001

Mike Pearson: I don’t mean that that’s manipulative - we don’t do that - but I certainly feel that’s the case with something like ‘‘Rain Dogs’’. Equally, you are quite right. We are fortunate to have in Wales a whole generation of actors who have made most of their career in television - in Welsh television. And so they are very clever at being present for two seconds for the camera in a cut-away, or whatever. I was talking to [John Rowley] yesterday - when you begin to work with them, they can give their attention to a camera without demanding that in-depth attention back. As performers get experience with media they know they can’t address the world ‘out there,’ so they address some portion…

Carrying Lyn, 2001

Gabriella Giannachi: For instance, it was quite visible from the fragment of Carrying Lyn that I saw that the people you encountered on the street were not particularly attentive, whereas the audience in the theatre cheered when you arrived

Mike Pearson: But in the moment of articulation on the street, I was closer to them.

Gabriella Giannachi: For me there’s a very interesting dynamic there. You were closer to the people on the street. The people who were with you on the street were far away from you, while the audience in the theatre, who encounter these events in their mediation, were closer to you.

Mike Pearson: Yes that’s true.

Mike Brookes: Again, it comes back to whether we accept this mediatisation as evidence. As Mike would say, as soon as it gains a kind of authority through having been registered - or having been looked at through CCTV - this artefact is more than a rumour from the street - it’s of a different order.

Nick Kaye: There’s another mechanism in there, also, isn’t there? Which is a transposition of the multi-temporality of the site into an explicitly multi-temporal structure realized in the performance.

Mike Pearson: Yes.

Nick Kaye: That has a major impact on the way the performance is perceived.

Mike Pearson: Yes, absolutely. Then I wonder if the implication of that complexity is that the performers have to do something fairly straightforward - perhaps even simple. To try and perform with that complexity might be extremely counter-productive. I don’t quite know what that would be - but if I decided I would try and address every single audience who might be looking at me in this moment, as opposed to developing a fairly arduous task-based work that can be looked at in different ways that might be…

Carrying Lyn, 2001

Nick Kaye: I was also interested - just to pick up something from earlier – in the distribution of the performer across recorded and live events, and so across different times and spaces. Do you think it amplifies or changes the quality or perception of presence?

Mike Pearson: I think it does, because in asking the performer to do that range of things - to distribute their work and to interrupt their work and fracture it in all these different kinds of ways - there is a need for a lot of reassurance. As soon as the performers become divorced from the effects they are generating, for being directly responsible to the audience, it can be a very, very lonely task indeed. And certainly working with the students in Germany on ‘‘Metropolitan Motions’’, that was very hard. It was almost as if one had to talk the performers down at the end of doing it and reassure them that things had happened at the same time that they were doing their thing - that things ‘’had’’ come together. Because, of course, there’s no way for them to monitor these things - so it may also require a different attitude to the task that one is undertaking.

Images by Mike Brookes. Reproduced with permission.

Back to Mike Pearson and Mike Brookes