'According to a national database, there are several people in the United States named Lynn Hershman.'

Lynn Hershman

“A seminal artist who has influenced our era, nationally and internationally”

Lawrence Rinder, Whitney Museum of American Art

"Her work appeared institutionally and visibly several years before Cindy Sherman but what makes Hershman different from the more obvious strategies of Andy Warhol and Cindy Sherman (which slide along the surface of things) is her profundity. Hershman was willing to take a risk “

Amelia Jones Professor of Art History, Manchester University, England

“A visionary filmmaker, we strongly believe Lynn is a significant voice in independent cinema”.

Michelle Satter, Sundance Institute

“Brings new vernacular to contemporary independent film… all in all it’s that rare sci-fi tale that actually leaves us wiser about our own time."

B. Ruby Rich, Sundance Catalogue

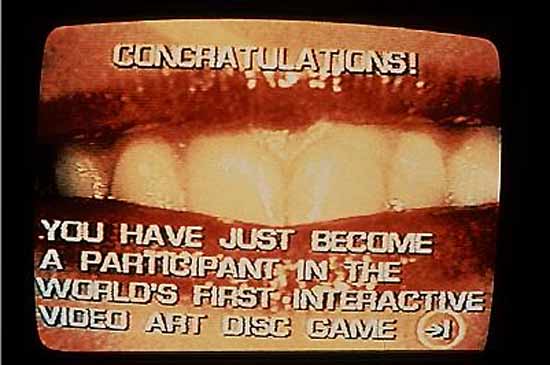

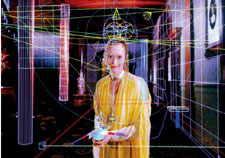

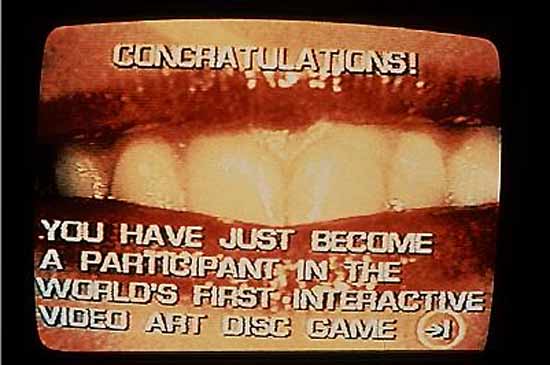

'Hershman has been at the forefront of “new media” art since the 1970s, developing fluency in new digital technologies as they evolved. She has been responsible for a number of technological innovations, including the first interactive computer-based artwork (Lorna, 1979-82), the first artwork to use touch-sensitive screen technology (Deep Contact, 1984-86), and the first networked telerobotic art installation (Difference Engine #3, 1995-99). Because of these breakthroughs Hershman is best known as a digital or “new media” artist. Many of the ideas embodied by Hershman’s artwork have seemed ahead of their time.'

Robin Held, Curator, Seattle Art Museum.

"Hershman’s is a prolific project of self-analysis and self-mythification that, through technologies of vision, multiplies and refracts fictional identities to the point of undermining any stable notion of identity. The trajectory of her work provides one of the better artistic mirrors we have for fragmented human subjectivity at the beginning of the 21st century."

Getty Foundation Grant Statement

When does presence become trace?

What is the politics of presence?

How dependent is presence on the viewer/spectator?

What constitutes presence within a mixed reality environment?

How located is presence?

What is necessary for AI to create a sense of presence?

How much can presence fragment before it disappears?

What happens to presence during the process of its (re-)mediation?

Dante's Hotel (1973-4)

Dante's Hotel was 'staged in a run-down residence hotel in San Francisco'. Hershman 'rented a room, furnished the interior with the personal belongings of an invented tenant and then allowed visitors to explore these objects to flesh out the inhabitant's identity, past and present.' (Held in Tromble, 2005: xvi)

Photo credit: Edmund Shea

Hershman writes: 'Eleanor Coppola [link] and I rented two rooms in a run-down hotel in the Italian section of San Francisco. Visitors entered the building, signed in at the desk, and received keys to the rooms. Residents to this transient hotel became part of the exhibition' (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 20)

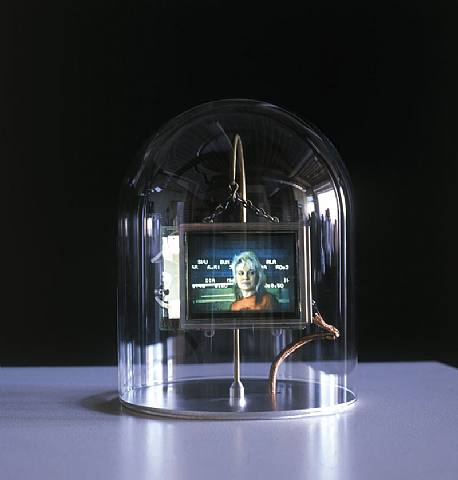

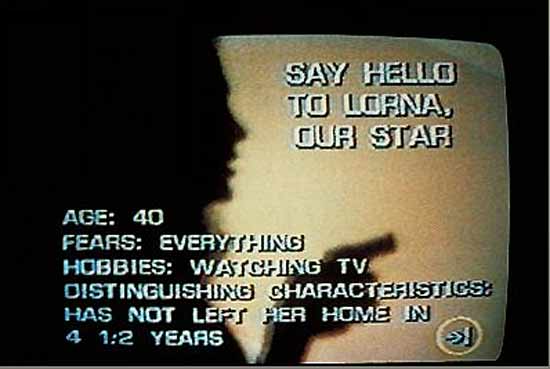

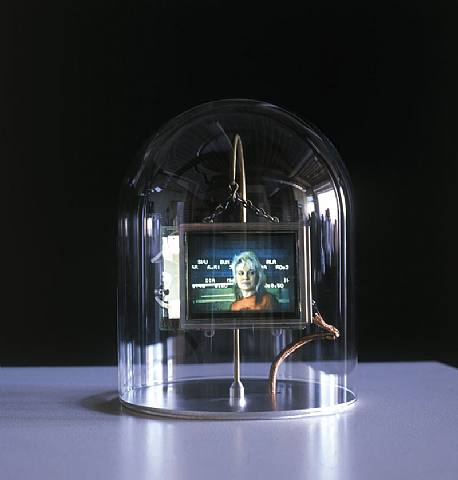

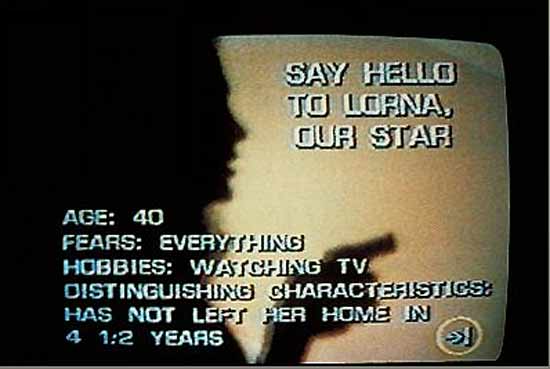

Lorna (1979-82)

'Lorna combined performance, narrative, time, chance, and participatory choice' (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 77)

The piece was one of the earliest interactive environments that engaged with non-linear film narrative. The viewer was seated is an area imitating a small and slightly claustrophobic lounge, containing furniture, a television set and personal objects such as a fish bowl and pictures.

Here, the viewers could interact with the television set by selecting specific objects on the screen and clicking on them with a remote control. By exploring the scenarios behind these objects, the viewer was able to put together the story of Lorna, a woman living in loneliness and desperation. In fact the only contact Lorna had with the world was through her television, just as the only contact the viewer had with Lorna was also mediated by the television.

The story was constructed through various plot lines so that it was the viewer’s decisions that determined the plot’s actual development (Dinkla, 1997: 191). As in Hershman's own words, ‘the action was literally in (the viewers’) own hands.’ (2003).

The installation worked like a hypertext and, as observed by Soke Dinkla, in the video, the furniture even had details which it did not have in the real. This slippage between the virtual and the real, which were presented as similar but not identical, manifested itself in the fact that in the virtual the bowl contained a fish which was not there in the real and, likewise, the virtual drawers were full of papers whereas in the real the drawers were empty (1997: 191).

Through Lorna, Hershman drew the viewers’ attention to the fact that not only had everything in Lorna’s life been swallowed up by the world of the medium but also that in the course of the process of mediation ‘real’ detail had been lost, so that ultimately the real and the virtual could not be seen as overlapping. In fact here, it is the virtual, the mediatised world, that constitutes Lorna’s ‘real’. In other words, it is the virtual (Lorna’s real) that has more detail than the real (the viewer’s real).

In Lorna the spectator becomes a voyeur, reconstructing Lorna’s life from the real and the virtual objects in both the real an the virtual room (ibid.). Moreover, from the loss of real detail through the process of mediation, the viewer is able to draw further information about Lorna as a being existing through mediation alone. And while the viewer could carefully move though the plot of Lorna’s fragile existence, they themselves could also become the focus of other viewers’ attention. It is possible for further viewers not only to watch Lorna’s life on the television screen but also to observe the ‘active’ viewer’s interaction with her. Watching Lorna thus entails the possibility of seeing not only the life of Lorna but also the viewer’s own reconstruction of her life.

Interestingly, navigating the piece is quite difficult not only because of the multiple variations offered by the plot, but also because the plot includes the possibility of being caught ‘in repeating dream sequences’ (anon, 1994: 3). Here, ‘the medium is the person’ (Schwarz, 1997: 123) and everything the viewer does or sees is received through the medium, i.e., it is in fact inside the medium.

Photo credit: Marion Gray

This is reflected in the fact that the story line offers three possible outcomes. In Hershman’s words, these were: ‘Lorna shoots her television set, commits suicide, or, what we Northern Californians consider worst of all, she moves to Los Angeles.’ (Hershman, 2003). Here, even death comes through the medium (Schwarz, 1997: 123): in fact Lorna could only but destroy the television set, thus ending her relationship with the outside world; commit suicide, which again implies the end of the medium, or move to Los Angeles, the city of Hollywood, the hyperreal – mediatisation.

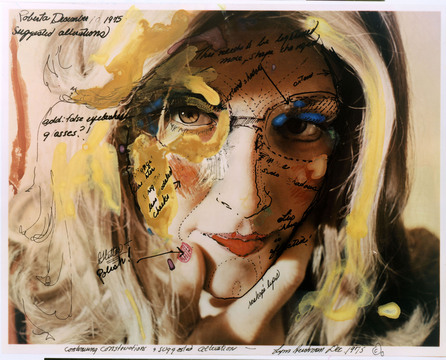

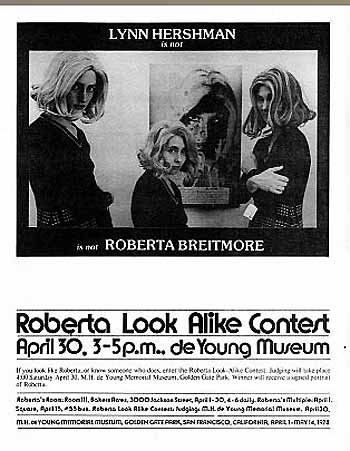

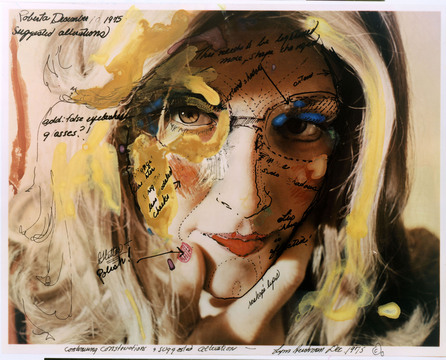

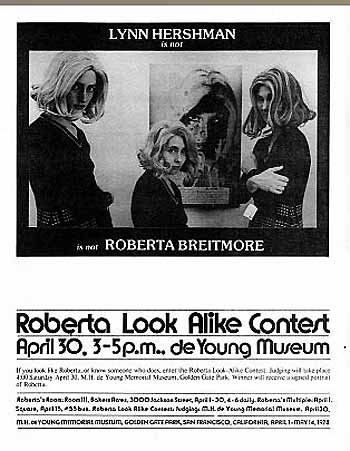

Roberta Breitmore (1974-1978)

The piece has been described as ‘an early excursion into virtuality, straddling the boundary between fiction and reality, or art and life’.

The character of Roberta was ‘at once artificial and real. She had a history which continually wrote itself anew, registering and documenting real experience, and leaving tangible traces of its existence.’

In Roberta Breitmore, Hershman herself became Roberta Breitmore, thus creating a persona who had an identity, a physical embodiment, but even ‘a set of individual gestures, needs and fears’ (Rötzer in Schwarz and Shaw, 1996: 136). 'Roberta was "born" when she arrived in San Francisco on a Greyhound bus and checked into the Dante Hotel. She carried in cash her entire life savings of $1,800.' (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 25)

In fact, Roberta had credit cards, an apartment, she corresponded with people and established relationships with them. She even put a small announcement in a newspaper in which she advertised for a roommate. The people who replied to the advert then became part of her fiction (Hershman Leeson, 1996: 330). Hershman indicates that Roberta accumulated 43 letters from individuals and had 27 adventures (2003).

She also points out that 'her childhood data was established before she was released into the world. ROBERTA reflected the values of her culture. She penetrated trends such as EST, WEIGHTWATCHERS and most significantly, experienced resonant nuances of alienation. Roberta saw a psychiatrist, had her own language and handwriting, apartment and clothing, gestures and moods.' (ibid., original emphases)

Described as the ‘private performance of a simulated persona’, Roberta was ‘at once artificial and real’ (Hershman Leeson, 1996: 330).

Hershman also hired three additional women to play Roberta: 'All three performers wore wigs and costumes identical to the ones worn by Hershman Leeson as Roberta. Each had two home addresses and two jobs - one for Roberta and one for herself - and each corresponded with respondents to the advertisement and went on dates that were obsessively recorded in photographs and audiotapes (...) All four Robertas existed simultaneously for a short time, until Hershman-Leeson ceased performing as Roberta, leaving three.' (Held in Tromble, 2005: xiii)

Roberta was finally exorcised in a 1978 performance at the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara [link]. Today we are left with her effects, photographs, artifacts and ashes.

Despite Roberta's exorcism, there are traces of her that can be followed, even now.

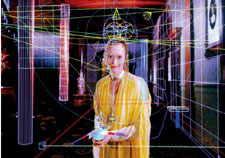

CybeRoberta (1995-8) and Tillie, the Telerobotic Doll (1995-8)

In the internet project related to the figure of Roberta, CybeRoberta, her fictional persona is, as in Hershman’s words, ‘designed as an updated Roberta’ who not only navigates the internet but is in herself a creature of the internet, a cyberbeing.

Here, Hershman points out, ‘surveillance, capture and tracking are the DNA of her inherently digital anatomy. They form the underpinning of her portrait.’ (Ibid.: 336). Thus whereas in Roberta Breitmore, Hershman was quite clearly performing Roberta, in the internet version of the piece Hershman’s ‘performance’ was curiously invisible, since on the internet everybody, not just Roberta, embraces character and adopts one or multiple personae.

'By looking at the world through the eyes of Tilie, viewers become not only voyeurs but also virtual cyborgs, because they use her eyes as a vehicle for their own remote and extended vision' (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 87)

When CybeRoberta and Tillie were exhibited together they pirated each other's information, thus causing a 'blurring' of identities (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 87)

'Tillie, a tpical feminine-looking doll, stares at you from the web site of the San Francisco based artist Lynn Hershman Leeson. Each of Tillie's eyeballs moves slightly as you move th cursor on it. Click on her eye and an image of a gallery wall appears in a window below. The dolls eyeballs have been replaced with cameras that send images to the Internet. Through Tillie's eyes you can look around the gallery, turning her head to get the view you want. You can also visit the gallery itself and watch the physical Tillie in front of you. You will see your own image physically reflected in Tillie's eyes, but you are also being watched by countless unknown Internet users behind her, whoc are using Tillie's face as a mask and watching you through her eyes.' (Kusahara in Goldberg, 2000: 203)

America’s Finest (1993-5)

This piece is an interactive installation in which the viewer encounters a rifle located upon a pedestal. Upon trying to use the rifle, the viewer sees a montage of pictures that includes a child, historical photographs from conflicts in which the rifle has been used, images from the museum or gallery walls in which the piece is located and finally themselves, seen from a variety of angles, while they are pointing the rifle.

The weapon presented is the M16 which was used in Korea, Vietnam and the first Gulf War. This weapon is in fact interactive and simply by looking though the scope and pulling the trigger the viewer ‘enters the field of fire’.

Here, the role of the killer and the victim are not only intertwined (Dinkla, 1997: 194) but quite literally reversed. Thus Hershman points out that in America’s Finest ‘if you shoot (…) the child’s face appears with a target drawn on it in red’ while a voice says ‘don’t’, ‘it’s easy’, ‘shoot!’, ‘don’t shoot please’ – hence temporarily transforming the viewer into an active perpetrator. But the position of the viewer is rendered more complex by the fact that they themselves also appear on the screen, as if they had been suddenly spotted by someone else and were just about to be shot. The effect of the piece is therefore that ‘pulling the trigger turns the viewer into both an aggressor and a subsequent victim of his/her own actions’ (Hershman, 2003).

Nobody is innocent in this work, since the viewer is located simultaneously inside and outside the installation, both inside the virtual and in the real, so that a split, double existence is achieved and the final realisation that virtual conflict has consequences over the real is made possible.

Hershman’s work problematises the viewers’ position not only by exposing the way in which interactivity creates choices that in themselves have political consequences but also in revealing how this affects identity both in the virtual and in the real world.

Identity, Hershman notes, is ‘the first thing you create when you log on to a computer service. By defining yourself in some way, whether through a name, a personal profile, an icon, or a mask, you also define your audience, space, and territory.’ (Hershman Leeson, 1996: 325).

On line, Hershman shows, everyone is performing and this is why, as she suggests, 'masks and self-disclosures are part of the grammar of cyberspace. They are the syntax of the culture of computer-mediated identity, which can include simultaneous multiple identities or identities that abridge and dislocate gender and age. One of the more diabolical elements of entering CMC or virtual reality is that people can only recognise each other when they are electronically disguised. Truth is precisely based on the inauthentic!' (Hershman Leeson, 1996: 325)

Conceiving Ada (1999)

'The first film to use virtual sets' (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 97)

Teknolust (2002)

Feature-length film described as a 'digital-age Frankenstein tale' in which Tilda Swinton plays four characters often seen on screen at the same time.

'The geneticist Rosetta Stone (looking like a dowdy version of Hershman Leeson) concocts a recipe that allows her to download her DNA into a computer program and create from it three clones, or "self-replicating automatons" (SRAs), each of whom is both sister and daughter to her'; 'not quite machine and not quite human, these three SRAs - named Ruby, Olive and Marinne after the red, green, and blue pixels used to create color on computer monitors - quickly begin to develop their own selfhood and pursue their own adventures.' (Held in Tromble, 2005: xiv).

Agent Ruby (2002)

[link]

Animated web-agent existing on a variety of sites. She is a 'self-breeding autonomous artificial intelligence Web agent shaped by encounters with users. She is thereby part of both the real and the virtual worlds. Ruby converses with users, remembers their questions and names, and has moods corresponding to whether or not she likes them' (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 92)

There is also a sculptural installation, Agent Ruby 2 (2004) which is able to respond to users' typed questions. Ruby can be replicated on a Palm handheld computer.

'In each stage of Ruby's development, shes expands her intelligence, her understanding of human emotion, and her verbal communication skills. (...) This Tamagotchi-like creature is an Internet-bred construction of identity that develops through cumulative virtual use, reflecting the global choices of internet users. Agent Ruby evokes questions about the potential of networked consciousness, identity, corruption, redemption, and interaction' (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 94)

DiNA

'an artificially intelligent bot running for the office of Telepresident' (Hershman Leeson in Tromble, 2005: 95)

DiNA processes internet contents in real time and responds to current events.

Many above abstracts are from Gabriella Giannachi (2004)

Virtual Theatres: an Introduction, London and New York, Routledge, pp. 139-44.

[link]

See also ZKM's record

[link], a resume and biography

[link], notes at Foundation Langlois

[link] and the Walker Art Museum

[link], Sweeney Art Gallery

[link], UC Davis

[link], and a recent article from rhizome

[link].

For an online interview see also

[link]

All images courtesy Lynn Hershman

References