Interview recorded 7 October 2007, UC Berkeley, edited by

Ken Goldberg and

Nick Kaye

Tele-Actor

Tele-Actor (2001). Courtesy of the artist.

Nick Kaye: How have notions of presence been important to your work?

Ken Goldberg: I think about presence in the context of “telepresence”, where one can experience a remote environment via some form of remote control. Radio controlled machines date back to Nikola Tesla in 1898, and of course the telephone in the mid nineteenth century. The oxymoron “telepresence” was first used by Marvin Minsky in 1980. 3G and 4G cellphones will soon make live video ubiquitous, so this is a good time to study presence. “Presence” comes from Latin “prae” (before) and “esse” (to be): so there’s quite a bit of unpacking to do.

Nick Kaye: Coming in part from a theatrical point of view, it is very interesting to me that there is always the suggestion of something embodied in your work, although it is usually at a distance from the participant or viewer. I wondered why it was important that there should be a material presence incorporated into your work?

Ken Goldberg: I’m interested in boundaries where abstraction meets materiality. Maybe it was growing up Jewish in a Pennsylvania steel town. My research is also at this boundary; my students and I develop geometric algorithms for robots and manufacturing. Although my artwork is conceptual and uses new media, it always has a physical, embodied component. As you noted Nick, the physical component may be distant; I use the term “distal reality” to distinguish the resulting experience from “virtual reality”.

Nick Kaye: These questions are very interesting with regard to presence. It reminds me in some ways of the issues raised by artist Gary Hill. Reena Jana wrote in Art Forum that: “If Bill Viola and Gary Hill brought video out of the box and into the realm of installation, Ken Goldberg has done the same for Net art.”

Ken Goldberg: All artists are escape artists, we’re looking for new ways out. The screen is a box, filmmakers and media artists pore over it in the same way that minimalists pored over wood and canvas. The screen is a limitation, an obstruction in the sense of Von Trier’s Five Obstructions. The challenge is to establish a presence beyond the box. The theatre is also a box; in Ballet Mori (2006) we used a seismometer and live network to bring the raw materiality of the earth into the San Francisco Opera House.

Ballet Mori

Ballet Mori (2006), San Francisco Opera House,

4 April 2006.

Ken Goldberg: I’ve been talking with philosopher Hubert Dreyfus about the experiential difference between theatre and cinema. We’re neither film nor theatre theorists; we defer to experts like you Nick, but from our naïve perspective: both theatre and cinema are collective experiences for the audience. Clearly the experience for an actor is very different: being on a film set in contrast to being in a theatre before a live audience. And there is a difference for the audience also. Most people are willing to pay a large premium to go to the theatre: no one claims that the two experiences are interchangeable. But what is the difference?

One theory is that the theatre offers risk: every performance is unique so there’s an element of uncertainty. This is certainly true for sports events, where one doesn’t know how the game will turn out, and in car races and circuses where there’s always a possibility that someone will get hurt. But is risk really why we crave the theatre? Imagine a film that offers some form of uniqueness: where there are many versions of the film and you never know which one you’ll get, or a film where there’s a chance the film will burn up at some point: so you create an element of risk, but that doesn’t seem equivalent to being at the theatre.

Risk certainly focuses attention. In The Present Age, Kierkegaard wrote: “Come on, leap cheerfully, even if it means a lighthearted leap, so long as it is decisive. If you are capable of being a man, then danger and the harsh judgment of existence on your thoughtlessness will help you become one.” I think one reason many kids are experiencing Attention Deficit Disorder is that on a daily basis we’ve reduced the risk in their lives.

Nick Kaye: So if not risk, what do you see as the difference between theatre and film?

Ken Goldberg: Dreyfus and I now suspect that it’s volition: in the theatre we as audience members continuously choose where to look on the stage, where to direct our gaze and attention. In the theatre, everyone is an actor: actively engaged in the act of perception. Gibson and Merleau-Ponty recognized that active perception fundamentally changes how we experience. It comes down to a matter of choice. I’m pro-choice.

Nick Kaye: Jerzy Grotowski , in Towards a Poor Theatre (London, Methuen, 1969): writes: "There is only one element of which film and television cannot rob the theatre: the closeness of the living organism. … It is therefore necessary to abolish the distance between actor and audience by eliminating the stage, removing all frontiers. Let the most drastic scenes happen face to face with the spectator so that he is within arm’s reach of the actor, can feel his breathing and smell the perspiration. This implies the necessity for a chamber theatre." (pp41-2)

Ken Goldberg: That’s great. Grotowski’s concerns about physical closeness relate to the issues of telepresence.

Nick Kaye: Speaking of film, popular film usually tries to overwhelm any doubt by presenting a very linear journey. In contrast, in your work you approach doubt as a mechanism and attempt to provoke this effect.

Ken Goldberg: Yes, I view doubt as a medium. It operates as a lens that sharpens experience. Suspending disbelief is great as long as you reclaim it on your way out. I’m interested in the resumption of disbelief.

As we discussed earlier, Jaron Lanier coined the term “virtual reality” (another oxymoron) in 1989 to refer to fictional but realistic 3D environments. VR is generated using computer graphics. With networks, sensors, cameras, and robots you can achieve “distal reality”: you are in one place, but you come into contact with a reality in another place. Telephones, televisions, and telerobotics are examples.

What does “presence” mean in these contexts? For the book The Robot in the Garden (MIT Press 2000), I collected essays from philosophers, engineers, and artists to reflect on this question. I was also trying to understand Walter Benjamin’s description of the aura of an artwork as “a persistent distance”.

Regarding doubt, Hubert Dreyfus suggested that internet-based telerobotics might re-invigorate Cartesian scepticism by providing plausible scenarios where your knowledge of an interactive and persistent experience might be illusory. We came up with the term “telepistemology” to describe a class of issues related to knowledge at a distance.

Nick Kaye: This seems very closely related to the issue of presence.

Ken Goldberg: Yes, and there’s still much to explore in the relationships between volition, perception, doubt and presence. Bishop Berkeley argued “esse est precipi,” – today almost everyone recognizes that the act of perception shapes experience.

Tele-Actor (2001).

Photo by Bart Nagel.

Ken Goldberg: Since 2001 I’ve been exploring how social dynamics enters into the equation. My colleagues and I developed what we called the Tele-Actor, a human equipped with sensors and cameras and communications gear that can interact with a remote environment and social event guided by input from remote participants. For example, a Tele-Actor could allow groups of disadvantaged students to collaboratively steer a telerobot through a working steelmill in Japan or the Presidential Inauguration, and allow groups of researchers to collaboratively explore a newly active volcano or a fresh archaeological site. By the way, more information on this and most of the projects we’re discussing is online at: http://goldberg.berkeley.edu

Nick Kaye: In some ways the processes you engage with seem to connect with a certain kind of theatrical dynamic. A multi-media theatre company such as The Builders Association is in some way a counterpart to some of the issues of embodiment that you address. They will present a live actor on stage and then disperse their performance out from that point in transmission or mediation, sometimes blurring distinctions between live and mediated or the materiality of the body and its projection, whereas you are promising to bring a distant material focus into view, to bring it forward into some kind of encounter despite its mediation. I thought that was a very interesting reversal and hence a connection to the theatrical, because you promise the concrete, the material or the embodied.

Ken Goldberg: We were talking about the differences between theatre and cinema earlier. There’s a similar issue in teaching. The experience for the student in a classroom is quite different from watching the same lecture later on a video or podcast. The podcast has advantages, it provides much greater access, especially to those who don’t have the option of going to the university. But we’re trying to understand what is the role of the live classroom experience, and we believe it’s the same answer: volition. In the classroom students must actively choose where to look, and there is always the potential to raise one’s hand and ask a question.

The Telegarden

The Telegarden (1995-2004, networked robot installation at Ars Electronica Museum, Austria.) Co-directors: Ken Goldberg and Joseph Santarromana Project team: George Bekey, Steven Gentner, Rosemary Morris Carl Sutter, Jeff Wiegley, Erich Berger. (Photo by Robert Wedemeyer).

http://goldberg.berkeley.edu/garden/Ars/

Ken Goldberg: In Marianne Weems’ work with The Builders Association as “media theatre” she explores the idea that the audience might be remote. One of the advantages, I think, is that it does let you potentially expand the audience across time and geography. What’s crucial is that you are not alone in the audience. In a networked art installation involving robots or cameras, when you talk about ‘audience’ there is the idea that you are very aware of others who may share the space with you. The co-presence of the audience is critical. When we developed The Telegarden (1995-2004) I was interested in the engagement between the person on the internet and the physical garden, but over time I grew more and more interested in the relationship between people who were sharing the garden.

Nick Kaye: Perhaps the unbearable thing about being the only person in a theatre is that you become aware of the performers’ awareness of your presence. In a sense with The Telegarden it seems that you may wish to become part of a community, so you may act in the hope of co-presence. It is as if you may want someone else’s awareness of your intervention.

Ken Goldberg: Yes, and this connects to a question of privacy. E.B.White noted in a 1948 essay on New York City that one can feel quite private in New York, in Central Park, on subways. It’s not like solitary confinement, where you are isolated from others, but you are anonymous: so you get community and privacy. As a meditation on privacy in public places, Demonstrate (2006) exposed the power of a new generation of surveillance cameras and its relation to the Free Speech Movement 40 years earlier.

Demonstrate Installation

Demonstrate Installation (2004-), Camera’s Field of View over Sproul Plaza, UC Berkeley

Ken Goldberg: As you suggest Nick, if I’m the only person in the theatre, and the actors are aware of me, I lose my privacy and this changes my experience of the play. It’s a question of the presence of others - we want the presence of other participants, other audience members, as part of our experience. In The Telegarden one can immediately interact with the robot and the garden, but to interact with the other people – that was always indirect.

Nick Kaye: One of the questions raised by The Telegarden is whether or not participants are really tending a garden. Did you find that people were very ready to believe in the garden?

Ken Goldberg: Most just jumped right in. But there were a few sceptics: how do we know there really is a garden? The first time it caught me by surprise. But I realized this is the fundamental question of epistemology: what can we claim as knowledge?

Ouija 2000

Ouija 2000.

Ken Goldberg: The issues of collective experience and doubt were the motivation behind Ouija 2000. It was in the Whitney Biennial and is still my most popular online installation: twenty to thirty people register to play it every day. Ouija boards provoke a range of reactions. Remember the excitement of playing with the Ouija board when you were a kid? It’s usually played late at a slumber party, and it conjures up the possibility of a third type of presence. There’s a distinct element of uncertainty and the intangible, why is this planchette moving? Is it trickery, is it our collective subconscious minds, or is the spirits - not spirits in a religious sense, but something that is a little bit in the air. It raises many of the questions that I’m interested in.

Nick Kaye: You have talked about the Ouija board as the earliest form of telecommunication. At the same time, it seems like a popular response to technology – an imaginary extension of technology’s ability to collapse distance and time, to make things present.

Ken Goldberg: Actually in the nineteenth century there was a huge discourse about “abolishing distance”. They were talking about the railroad, and technologies like photography and the telephone. When the telegraph and radio appeared in the late nineteenth century, one suddenly had the ability to hear distant and unseen voices – so it wasn’t such a stretch for people to believe that it might also be possible to speak with the dead.

Dislocation of Intimacy

Dislocation of Intimacy (1998-), Installation View,

Cambridge Art Centre, 2004.

Nick Kaye: This reminds me of your installation, Dislocation of Intimacy (1998). You begin your essay, ‘The Unique Phenomenon of Distance,’ in the introduction to The Robot in the Garden (MIT Press: 2000), with a quote from Walter Benjamin: ‘Every day the urge grows stronger to get hold of an object at very close range by way of its likeness, its reproduction.’ I was very interested in this because both the essay title and quotation implicitly refer to Benjamin’s notion of ‘aura’: ‘the unique phenomena of distance however close something may be.’ It seemed to me that Dislocation of Intimacy was explicitly about staging the auratic, because it presents that which is only available by choosing to be at a distance. There are all kinds of veils in the way.

Ken Goldberg: “Staging the auratic”…I like that. Benjamin writes about an ever-present distance. The aura or authority of a person or object that keeps us at a distance, no matter how close we are physically. Is it possible for something you experience on the internet to have an aura? In Dislocation of Intimacy, we built a minimalist black box to enclose a space and made it physically inaccessible. You could walk around the box in the gallery, and the idea is to create a desire, a curiosity about its interior. The only way to experience the interior is through the Internet, by visiting the website and viewing with the online camera and light switches.

Dislocation of Intimacy

Dislocation of Intimacy (1998-), interior view.

Nick Kaye: So one couldn’t get access to the Internet at the gallery.

Ken Goldberg: Right. One gallery said ‘We’ll just put a computer next to the installation’ – and I explained that would miss the whole point: you have to leave to be present. The idea was to create something simultaneously present and absent.

Nick Kaye: It also seems to tie together the hidden or distanced with a staging of aura and value.

Ken Goldberg: Exactly. I’m interested in drawing attention to presence through what can’t be immediately perceived. That is the motivation behind flw (1996). It is a 1/ 1 millionth scale microsculpture in silicon of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, it’s on exhibit in Paris right now. The installation includes an optical microscope, which isn’t quite sufficient to allow you to perceive it. It creates a distance in scale, rather than a distance in space. I’m trying to explore broader questions of distance and presence. Thinking about eighteenth century Cartesian scepticism led me to the microscope and to thinking about scale. In flw I wanted to create desire, curiosity, around something that draws you in, but then won’t reveal itself.

flw

flw (1996), microphoto

Nick Kaye: It’s interesting to me that you have a clear focus on embodiment, yet you have not as far as I am aware used your own body as an instrument, image or presence in your work.

Ken Goldberg: Actually I use my body in one project. I don’t normally talk about it. It involves keys. I wanted to create something personal and not precious in any way. I take people’s keys – only on a volunteer basis - and I rearrange them as we talk about them. Most people have keys on their keychains that they don’t recognize. People keep keys out of nostalgia, like the key to one’s last lover’s apartment or an old mailbox. So we discuss the keys, and I rearrange them and offer to put on colored rubber caps. I have boxes of colored caps and rings and attachments. I let the person choose everything, and it’s an ongoing process: I provide a free lifetime tuning service.

Nick Kaye: I’m interested in this feathering of work into the everyday - or the interruption of the everyday. It’s interesting of course that Displacement of Intimacy is related to Marcel Duchamp’s With Hidden Noise (1916), the "assisted ready-made" with the noise, the source of which is hidden in a ball of twine. I was thinking Duchamp’s work is very much about meaning being constructed in use - or the prohibition of use – the everyday object made distant by being re-framed as "art".

flw

flw (1996), installation vews, San Jose Museum of Art, August 2006

Ken Goldberg: Interesting. I share Duchamp’s interest in hardware stores. There’s definitely element of ready-made to the key project. With Hidden Noise and other readymades, the object’s functionality is altered. The key project is very pragmatic - maybe that’s my engineering side - because I want to enhance the object’s functionality. A key is a physical manifestation of identity, like your password. A key gives you access, privacy, vulnerability - and as a technology, keys haven’t changed in the last hundred years.

Nick Kaye: Speaking of vulnerability, did that issue arise with the Tele-Actor?

Ken Goldberg: Yes, being a Tele-Actor can be stressful – you’re wearing all this electronics and networking gear, which is physically tiring, the people you encounter may not understand what you’re doing and sometimes they can be a little hostile. And you are taking directions from strangers online. It’s like balancing twenty ids, egos, and superegos.

Nick Kaye: Do you think online participants gained a sense of this vulnerability? I noticed on the project site you see the words, ‘this is going to be conducted by a skilled actor’ – so I wondered if visitors may have felt protected from the vulnerability, because she is "skilled".

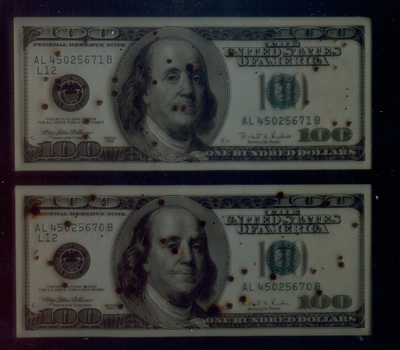

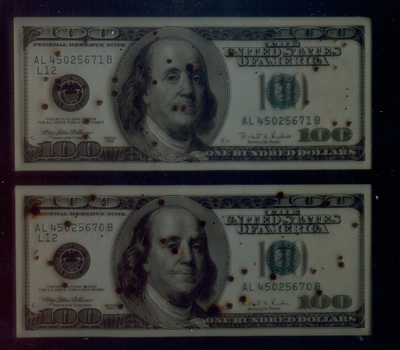

Ken Goldberg: I’d like to create even more vulnerability. We weren’t able to go as far as we hoped with the Tele-Actor because we were using analogue wireless television signals and they would get disrupted. Today we’d use 3G cellphone technology. We explored the issue of vulnerability in Legal Tender (1996), with Mark Pauline, Eric Paulos and others. It was an online laboratory. Visitors were presented with a pair of US$100 bills and told that one was real and the other counterfeit. Users could perform experiments on the bills by registering with an email address. After receiving a password, the user was assigned a random sector on either bill A or B along with a magnified view of that sector: Users were then invited to choose an experiment to perform on their sector. After choosing an experiment, users were reminded of the following law and asked if they want to proceed. Title 18, Section 333: Mutilation of National Bank Obligations: "Whoever mutilates, cuts, defaces, disfigures, or perforates, or unites or cements together, or does any other thing to any bank bill ...shall be fined or imprisoned." We wanted to create a sense of vulnerability and accountability through habeas corpus, to actively engage the body of the online visitor.

Legal Tender

Legal Tender (1996), Two Bills

Nick Kaye: When we began this conversation you made a distinction between the experience of "virtual reality," in the context of Second Life, and "distal" reality. I was wondering how something like CAVE fits into this, where you are in an environment which is explicitly "virtual" but in three dimensions so with a heightened sense of closeness or immediacy?

Ken Goldberg: Second Life is screen based, but prior VR used the goggle and gloves to create an immersive element. But that element of immediacy and intimacy is definitely worth exploring. I’m interested in how identity is intimate. In Second Life, identity is very fluid. You come in and you take on an avatar and you can switch things about the avatar – essentially it is a place to explore identity. By the way, I’ve never liked the word “avatar”, I picture a cheaply made statue and the word avarice. Similarly, “virtual” should remind us of its root in “virtuous”, but instead it conveys falsehood in the sense of “pseudo.” Facebook is the opposite of Second Life. In Facebook, you start by positioning yourself within your network of friends–it’s not a masquerade.

Nick Kaye: Although this has been implicit in much that we have talked about, I wanted to ask you directly about how you see the relationship between your process toward the artworks and your research in engineering?

Ken Goldberg: I’ve been re-reading C. P. Snow’s The Two Cultures. Everyone has strengths and weaknesses - I have a tin ear, I can’t sing, I have all kinds of limitations - but one thing that comes easy to me is moving between these two cultures.

One similarity is that artists and engineers share a drive toward doing something that hasn’t been done before. One difference is that engineers, especially in an educational environment, are taught to explain their concepts in a crisp and unambiguous way, usually with mathematics. As an engineer I feel a strong responsibility to demystify technology. New technologies are so complex that they appear mysterious, “indistinguishable from magic” as Arthur C. Clark noted. But in art, explanation can be deadly. Doing an interview like this is probably a bad example because I’m saying too much. Artists need to practice restraint. It’s important to conceal a little, leave some things unspoken, to preserve some sense of distance.

Nick Kaye: That returns us to the way that presence is claimed, asserted or performed by something that that doesn’t exhaust itself in the telling or presentation.

Ken Goldberg: Yes, I like that. Presence requires absence. Maybe we should just erase this tape…

All images courtesy Ken Goldberg.

Back to Ken Goldberg