Interview recorded 9 November, 2007, Hudson, New York, edited by Nick Kaye.

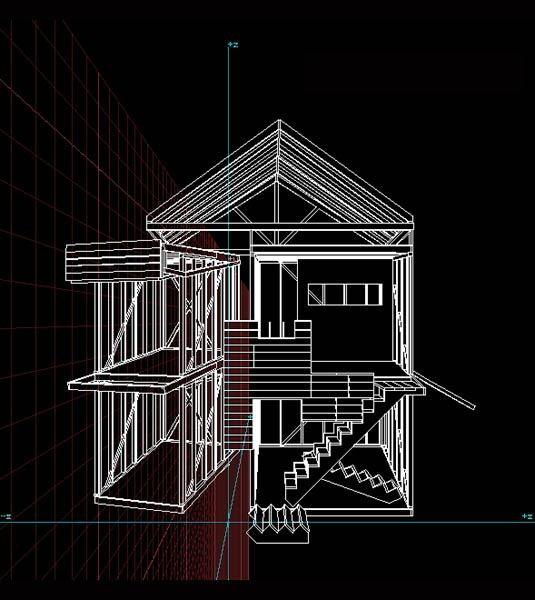

John Cleater, design for The Builders Association, Master Builder (1994)

Courtesy: John Cleater.

Nick Kaye: How did you begin working with The Builders Association?

John Cleater: It probably has a lot to do with the loft that I lived in at the corner of 9th Avenue and 14th Street. Marianne Weems had lived there, Larry Rinder from the Whitney and many other people – anyway, it was a kind of hub, where I met Marianne and I heard about the Master Builder proposal. When I heard references to Gordon Matta-Clark, Giotto and the story of The Master Builder, which I wasn’t familiar with, I just went out of my way to make sure I was involved.

Nick Kaye: Was Matta-Clark’s work of particular interest to you at that time?

John Cleater: Yes, absolutely. I mean I had an appreciation of his attitude towards architecture. At the time I was at Columbia getting my Masters and he had this kind of attitude that architecture wasn’t precious - really the opposite of the academic world. I really connected to that. I also have a construction background so I can relate to some of the building –that blurring with being an artist. He also went to architecture school briefly and I connected with his take on architecture as a conceptual art form.

Nick Kaye: What do you mean by architecture as a ‘conceptual art form’?

John Cleater: Partially because of my education with people at the Daniel Libeskind School and, in particular, as a student of Karl Chu at a time when Robert Stern and Michael Graves were driving a lot of people nuts, just picking pieces from the past. Post-modernism has a really negative aspect in the architectural world - very different, I think, from philosophical thinking, even from performance and the writing world. I always thought post-modernism was a point in architecture where people couldn’t figure out where to go, so they were picking and choosing pieces from the past. And the whole of Libeskind’s approach and education was trying to strip it all away, to find a way to start anew. In Karl Chu’s Studio we were trying to do these non-objective drawings, trying to just erase any reference to anything at all - and talk about architecture in a very serious, philosophical way. That was my background. So I still feel like architecture isn’t necessarily a building - and when I do theatre set proposals, installation art proposals and design buildings, they are all, kind of, ‘projects’. In that respect when The Builders Association first joined together I think a lot of us – Ben Rubin and I - had not so much of a theatre background. Master Builder was a ‘project’ more than it was a theatre piece - and I think that was one of the really exciting things about the formation of The Builders - to build the set and the house was a kind of research as an architect. It was a kind of temporary architecture. That is the way I think of performance.

Nick Kaye: So what was your starting point for Master Builder?

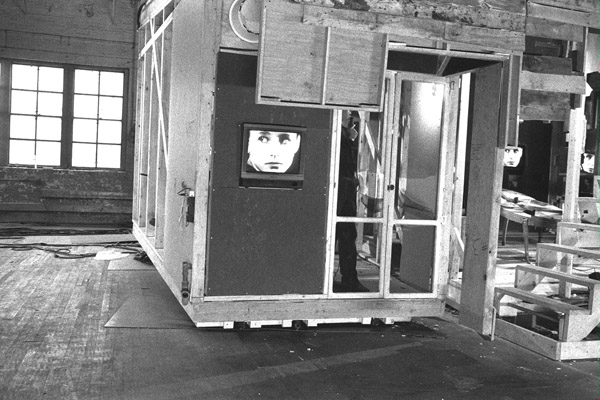

The Builders Association, Master Builder (1994)

Courtesy: The Builders Association

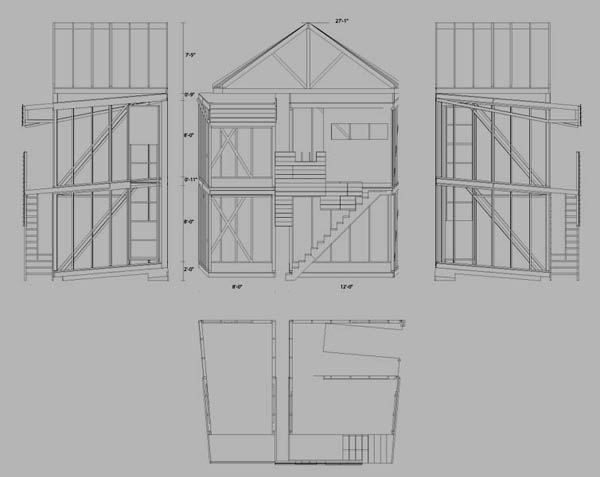

John Cleater: I was approached by Marianne and Jeff Webster who had just been in England, where they had seen a Matta-Clark exhibition - this was in 1993 or 1994, I guess. Of course, I was familiar with Splitting (1974) and they were really interested in turning this into a set. I am sure you are familiar with this famous collage, where he cut the image of the house in half and lifted it. In our case we cut it in half and rotated it - eventually. It was built in sections and separate pieces and we didn’t realise that we were going to want to literally split the thing at the end of the performance until after it was built.

Anyway, Jeff and Marianne came to me with the idea of translating the psychological breakdown that happens in the play The Master Builder to a physical breakdown of the set - and we talked about, you know, Matta-Clark’s actions and incorporating all that into the actual set as well as incorporating ideas of the de-perspective of the stage - an interest of ours seen in Giotto’s paintings. The set was built in a way that, rather than forcing a perspective, the walls kind of go apart from each other. It is the opposite of forced perspective, so if you are standing at one point it looks as if the walls are continually going in space and they never would meet. And at the same time, raking the floor. The appreciation of Giotto definitely had to do with that.

Nick Kaye: So in the Giotto there isn’t a single unifying point for the perspective. How was the floor raked?

The Builders Association, Master Builder (1994)

Courtesy: The Builders Association

John Cleater: It was raked in a conventional way, while the walls went back in an unconventional way, so it was confusing. It created an illusion that people were moving up and down rather than back and forth. I was really interested in playing around with these ideas between Giotto and Matta-Clark and it all came together for me in a particular way. I can’t remember exactly Marianne’s interest in Giotto - and also there is a Buster Keaton aspect, I think it is One Week (1920) - the film that delivered a house in a kit and he gets the numbers screwed up and puts it together wrongly so you end up with the kitchen on the outside. So we did that. We built it on a kind of rotating pedal – there were several parts of the set that were playing around with this inside-out idea.

Nick Kaye: And during the performance were parts of the house rotated?

John Cleater: It had all kinds of different things going on. We had one sidewall, which was borrowing from the Buster Keaton scene where he is leaning out of the windowsill upstairs and his wife is leaning on the windowsill downstairs. Then the whole façade falls and it rotates. I built a kind of rotating pinwheel. If I remember correctly, David Pence was leaning on it upstairs and played around with it rotating – flying around on it.

John Cleater, Master Builder, plans (1994)

Courtesy: John Cleater

Nick Kaye: How did it rotate?

John Cleater: The house was built so the pin was right in between the two floors – it was on a rod or steel pipe. I came up with as many different ways of the house either shifting and sliding – part of the side of the wall when you leaned on it would peel off to the side and would kind of come back. What I tried to do was make it so when the parts of the set were being physically manipulated they were happening from other rooms – so we had the peeling idea, the rotating idea, we had inversion, inside and out - where the kitchen could be on the outside. We had pieces that just got knocked and then we had the whole set split in half and rotate over. We tried to do as many different kinds of things as we could. There were also walls that got banged through –there were parts that would have to be redone each time, but most of it was easily reset.

Nick Kaye: How involved were you with the design of the system through which the actors’ actions would trigger audio or visual sequences?

John Cleater: Only in that I was really interested in how one thing would happen in one room, but it would affect the change in another room. And it was a pretty big set – it was a house.

Nick Kaye: Did engaging in this process advance your ideas around architectural practice?

John Cleater: Absolutely. I had done one thing before Master Builder that turned an architectural idea into a performance [Wax Tails, 1993]. It was just before computer animation. I made an animated model that was shot on 16mm film. I shifted things around an eighth of an inch and shot time-lapse of them moving. I thought of it as a documentary of a space.

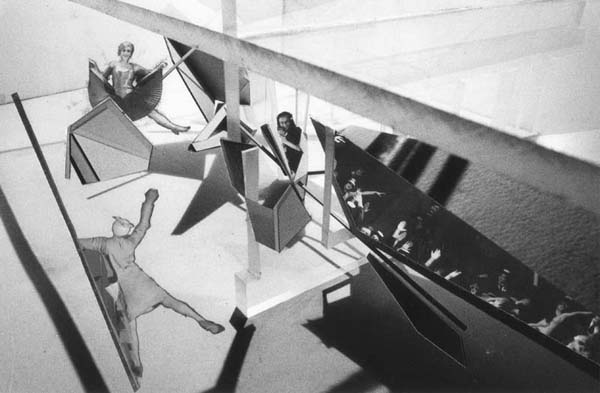

John Cleater, collage for Wax Tails (1993)

Courtesy: John Cleater

John Cleater: It was about translating volumes of sound into physical volumes of space. I made an architectural plan of this loft – this famous loft where I met Marianne - and at the time there were all kinds of noises. I mapped a lot of the different sounds that came into the loft from the streets. It is a big loft and at the time there were three apartments on that floor - and so neighbours would kind of walk through the middle of our space to get to the back door when the elevator wasn’t working, which was most of the time. So I drew these maps of sounds of people walking through the space – the toilet, the kitchen noises and where the TV was - and what happens is there is a lot of overlap – after they kind of bounce around in particular ways– they were always shooting at 90 degrees when they hit a wall. And there were several locations where they kind of coagulated and I built these sculptural things that were supposed to be this kind of intersection between invisible volumes – making them visible. Realizing that sounds are always moving, and rather than building some mechanical sculptures, I hired some dancers and made them moveable parts - so I turned it into a performance.

John Cleater, Wax Tails (1993)

Courtesy: John Cleater

Nick Kaye: It is very interesting that you describe it as a kind of documentation of the space.

John Cleater: That was really my beginning of understanding of multimedia and how you translate from sound to the visual – it was kind of comforting to know these forms weren’t coming from nowhere. Although they were completely abstract, they had a real reference. I think it may have been one of the beginnings of my fascination with working with sound myself - and I work with you know a lot of different art forms. There was a live band - a cello and strings – improvisational musicians. And they communicated with the objects that I had translated from the sounds of the space where it was being performed. The dancers were communicating between their movements.

Master Builder was really guerrilla style, completely illegal –we were totally DIY. We found this cheap space –

Nick Kaye: Built a three story house -

John Cleater: And we just invited people in to see it. The performance was in dead winter –you could see your breath. There was no heating – and hundreds of people came - and people talked about it. We had one of the carpenters who was helping me set up all the tools that we used – Joel Cichowski - he was a friend that ran the woodshop at Columbia Architecture School at the time. At the very beginning of the show, it opened up with him setting all the tools out on a table and he just showed how they worked, described what they were, and where they came from - how they were made.

Nick Kaye: And after the performance could people walk through the set and reactivate the triggers?

John Cleater: That is true – after the performance people were invited to walk through.

Nick Kaye: And then you designed Imperial Motel (Faust) (1996).

The Builders Association, Imperial Motel (Faust) (1996)

Courtesy: The Builders Association

John Cleater: That took in a lot of the moveable parts and ideas - we really got into blue screen –

Nick Kaye: How did that come about?

John Cleater: In terms of the set, that project went through several manifestations. The story of Timothy McVeigh - Marianne, Ben Rubin and I went to Vegas, rented a car and drove up to the motel on Route 66 where McVeigh had spent the week. He had rented this room and spent that week preparing to go blow up the Oklahoma City government building. So we were going after – what was he doing in that room? That was the kind of tension. We were kind of trying to make the connection between his feeling and the character of Faust. So the main set of Imperial Motel was this hotel room. A lot of the set came about as a armature of some video-like ideas – and again there was this interest, like in Master Builder, where we could see live performance happening in one space and then video, or some other kind of aspect, showing up in another space. A lot of that was an interest of mine - and how the Imperial Motel set worked. So the idea was there were these two main playing spaces on the stage and they weren’t necessarily connected – there might be a bar and a motel room, a bedroom - so we were referring to a few different spaces in different versions of Faust. There were these disparate things happening live on stage and this real interest in blue screen getting used and putting the blue screen set up on display so that you saw how it actually worked. You would see the camera, the set up; you would see the blue screen so the backdrops would change from a wallpapered motel room to just a blue room - it was just a series of these panels that were pulled out so each space would have a different background. So the idea was that you would see the whole set up –you would see the action here going on and you would see an action on the other side of the stage - then that came together seamlessly on this film above.

Nick Kaye: Presumably one of the things going on with the Master Builder is the exposure of the building, because the building is being pulled apart – you are seeing it as a sort of skeletal structure, in some ways. Then in Imperial Motel there is the exposure of the electronics – and the electronic processes.

John Cleater: I think Imperial Motel was really the beginning of the stage becoming a kind of armature for this media experiment to happen.

Nick Kaye: Then sometime later you were involved with Xtravaganza (2000). What was your involvement there?

John Cleater: Well, designing the set and, you know, again, I think the technology at that time on Xtravaganza was this Jitter program, this video altering software. Jitter does some interesting live effects.

Nick Kaye: It was a multiplication of the performance wasn’t it?

John Cleater: Yeah. I can’t remember if Jitter came first or the idea of working with Busby Berkeley. It was after Jet Lag (1998). I guess like in Jet Lag it was about creating a seamless relationship between live performance and the video and the attempt was to blur the relationship between the two.

Nick Kaye: What has the relationship been between your participation in these projects and your work that is not associated with The Builders Association?

John Cleater: I think my work with The Builders Association and simultaneously with Asymptote Architects [link] has a common interest in how one experiences the threshold between physical and virtual spaces. In my work with Asymptote, as with The Builders, there is this given that we are going to be up to date with the latest technologies and how they get infused into space, whether it’s theatre space or real architectural space. For me the great thing about the theatre is having the freedom to play with illusion. In the theatre you can do things that you can’t incorporate into real architectural space, but there is a lot to be learned. And there are very similar things going on, as I am sure you probably know. A lot of architects are obsessed with keeping up to date – you thrive on how the new technologies get embedded into your theatre set or into architecture. As you can see, one of the things that differentiates my architectural work from my designs for the Builders Association is, as an architect, I create new types of architectural form, whereas in the Builders' projects, at least up to now, we work with existing anonymous types of architectural forms yet present a new theatre form.

Nick Kaye: I was interested in the installation, Emergency Exit (1998) –

John Cleater, Emergency Exit (Artists' Space, 1998)

Courtesy: John Cleater

John Cleater: The installation was at the Artists’ Space [New York] was – it was a model that could be installed into any kind of building. Whether it is a really cool building or some old Soho business building, there are the same standards required for designing a stairwell. I was interested in using that as a site, conceptually – handrails could be activated and there was a kind of public access side and a private access side. And they were plugged in. The private one, for example, would be that you could access your particular company. Depending on what floor you are on, you may on that handrail be able to access information on meetings you have the next day - and these would be projections on the walls as you were going down and hidden audio. So that was one side of it. The other side was more public information; more general kind of world news and traffic - things that are going on between here and the airport - that kind of information retrieval system.

But the way I had the installation at Artists’ Space set up was much more conceptual and theoretical. I was interested in the alchemical masters that talked about light. I set it up so there was a camera and so your figure would be superimposed out into the ether. That was superimposed onto some information about light and darkness from this great book, Alchemy and Mysticism. Then on the other side I talked about all the specifics of the materials I used to build the installation, which were lasers and sensors – it was very literally about what the installation was. So I have this kind of obsession with complete abstraction and, you know, clear simple descriptive qualities of the materials of things.

Nick Kaye: I was very intrigued by the forms you have been creating very recently –

Architectural Appendages, created by John Cleater at Kohler Co. as a JMKAC Arts/Industry resident 2007.

Courtesy: John Cleater.

John Cleater: I called them architectural appendages. I was awarded a residency at the Kohler Foundry in Wisconsin. I think from my earliest drawings I have been fascinated with the body; in Wax Tails, for example, the way that they were made were like large pieces of costumes that would unfold and had a kind of architectural space in reference to like the Constructivists, where the relationship between theatre, architecture and art was really clear.

Architectural Appendages, created by John Cleater at Kohler Co. as a JMKAC Arts/Industry resident 2007.

Courtesy: John Cleater.

Nick Kaye: Some of the drawings for the architectural appendages seem to be about capturing processes of movement.

John Cleater: Yeah - there was a fascination in the relationship between the body and architecture and the body in an urban scale. And the way all the parts of your body work, as well as forms that you are familiar with and how they get translated into different scales of building. Part of the intention was definitely an extension of some of the things that I was working on with Asymptote.

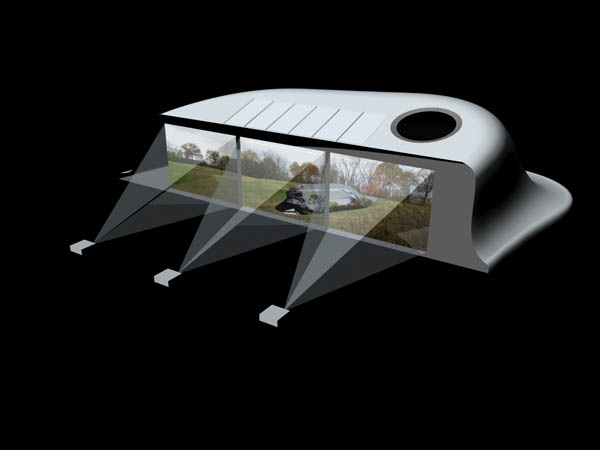

John Cleater, Architecture OMI video projection pavilion proposal (2007-8)

Courtesy: John Cleater.

John Cleater We had a similar fascination and interest in design that breaks the definition of scale. Each was designed as something you could go inside - or even larger - so that was going on in terms of the particulars of the forms and the shapes I was working on. But all of those forms are derived from a couple of Kohler products – sinks that I had kind of re-projected using 3-d modelling software onto different surfaces and then rebuilt them. I went there thinking - how do you turn a product into either the scale of a large building or a car, or a device of some sort, but all the while addressing them as one-to-one actual scale objects as kind of pseudo-products that are elusive, evocative, suggestive forms that make one ask ‘how does it work?’ or ‘what is that suppose to be?’ I am currently using some of the appendages forms in a scaled up version as a proposal for a video projection pavilion at Architecture OMI [link], a sculpture park two hours north of NYC.

John Cleater, Architecture OMI video projection pavilion proposal (2007-8)

Courtesy: John Cleater.

John Cleater is a founding member of The Builders Association and has created designs for many of their cross-media productions. His architectural work is wide ranging, and includes work as a project architect with Asymptote for clients including the New York Stock Exchange, Documenta XI, BMW Headquarters, The Guggenheim Virtual Museum, and Carlos Meile. While at the Columbia University School of Architecture, where he gained his Master's degree, he oversaw, with Hani Rashid, the creation of three large-scale interactive installations in the American Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2000. His recent work includes Emergency Exit at Artist Space in New York, as part of the critically acclaimed exhibition Digital Mapping in Architecture. He has also worked on projects for Daniel Libeskind, Bernard Tschumi, Vito Acconci, I.M. Pei, and others. Cleater redesigned Brooklyn College Gymnasium for the Brooklyn College Community Partnership program by creating large cut-outs shaped from popular logos as well as designed a mobile stage/ seating. In 2007, he held a John Michael Kohler Arts Center residency at the Kohler Foundry where he created large Architectural Appendages out of enameled iron and chrome plated brass that will be incorporated into an unfolding, self-sustainable mobile container for multiple uses. Currently Cleater is involved on the advisory commitee at the OMI International Arts Center's newest project, Architecture OMI: Exploring the Intersection of Art and Architecture.

John Cleater's extensive website is at [link]

For further discussion of The Builders Association's Master Builder go to Marianne Weems, SUPER VISION interview and Nick Kaye, Architectures of Presence.